By Raymond

Chickrie

HISTORY,

TRADITIONS,

CONFLICT

AND

CHANGE

Introduction

The

birth

of

Islam

in

Arabia

and

its

later

spread

to

South

Asia

and

Africa

had

rippling

effects

not

only

on

that

region's

social

and

political

history,

but

international

ramifications

as

it

spread

from

there

to

other

parts

of

the

world,

including

Guyana.

Islam

travelled

to

the

shores

of

Guyana,

Suriname

and

Trinidad

largely

because

of

the

institutions

of

slavery

and

indentureship.

Guyana

is a

multi-ethnic

republic

situated

on

the

northern

coast

of

South

America

(see

Figure

1).

The

country

is

inhabited

by

nearly

one

million

people

who

are

heterogeneous

in

terms

of

ethnicity

and

religious

affiliation.

Amerindians

are

the

indigenous

people

of

Guyana.

In

the

seventeenth

century

the

country

became

populated

by

waves

of

immigrants

brought

in

under

colonialism

which

introduced

plantation

slavery

and

the

indenture

system.

Thus

the

Dutch

and

later

the

British

colonial

mercantile

interests

shaped

the

socio-cultural

environment

of

the

country.

Guyana

remained

a

British

colony

until

1966

when

it

achieved

independence,

which

marked

the

transfer

of

political

power

to

the

Afro-Christian

population.

However,

the

majority

are

of

South

Asian

descent

and

form

roughly

51%

of

the

population

(see

Figure

2).

Yet,

they

remained

disenfranchised

until

the

1992

general

elections.

|

MAP: Fig. 1. Guyana: administrative divisions, 1991.

|

South Asians, who are mostly Hindus and Muslims, have always had a cordial relationship among themselves. It would seem that these two groups had come to a mutual understanding of respecting each other's space while culturally and even linguistically identifying with each other. In fact, Hindus and Muslims share a history of indentured labour, both having been recruited to work in the sugar cane plantations. They came from rural districts of British India and arrived in the same ships. Furthermore, Muslims and Hindus in Guyana did not experience the bloody history of partition as did their brethren back in the subcontinent. Also, the lack of Hindu/Muslim friction in Guyana may be attributed to the Cold War and to their common foe--the Afro dominated government, which practised discrimination against them (for religious composition, see Figure 3).

According to the Central Islamic Organization of Guyana (CIOG), there are about 125 masjids scattered throughout Guyana. Muslims form about 12% of the total population. Today in Guyana there are several active Islamic groups which include the Central Islamic Organization of Guyana (CIOG), the Hujjatul Ulamaa, the Muslim Youth Organization (MYO), the Guyana Islamic Trust (GIT), the Guyana Muslim Mission Limited (GMML), the Guyana United Sad'r Islamic Anjuman (GUSIA), the Tabligh Jammat, the Rose Hall Town Islamic Center, and the Salafi Group, among others. Two Islamic holidays are nationally recognized in Guyana: Eid-ul-Azha or Bakra Eid and Youman Nabi or Eid-Milad-Nabi. In mid-1998 Guyana became the 56th permanent member of the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC). Guyana's neighbour to the east, Suriname, with a Muslim population of 25%, is also an OIC member state. |

The

Arrival

of

Islam

in

Guyana

Islam

was

formally

reintroduced

in

Guyana

with

the

arrival

of

South

Asian

Muslims

in

the

year

1838.(n1)

Yet

one

cannot

dismiss

the

fact

that

there

was

a

Muslim

presence

in

Guyana

even

earlier

than

that

date.(n2)

There

were

Muslims

among

African

slaves

who

were

brought

to

Guyana.

Mandingo

and

Fulani

Muslims

were

first

brought

from

West

Africa

to

work

in

Guyana's

sugar

plantations.

It

is

also

said

that

in

the

1763

rebellion

led

by

Guyanese

national

hero

Cuffy,

that

the

terms

and

conditions

for

peace

that

Cuffy

sent

to

the

Dutch

were

written

in

Arabic

and

this

would

indicate

that

there

were

Muslims

among

Cuffy's

group

or

that

Cuffy

himself

might

have

been

a

Muslim.

However,

the

cruelty

of

slavery

neutralized

the

Muslims

and

the

practice

of

Islam

vanished

until

the

arrival

of

South

Asians

from

the

Indian

subcontinent

in

the

year

1838.

However,

to

this

day

Muslims

in

Guyana

are

referred

to

as

Fula,

linking

them

to

their

West

African

ancestry.

Mircea

Elida

writes

that

`

from

1835-1917,

over

240,000

East

Indians,

mostly

illiterate,

Urdu-speaking

villagers,

were

brought

to

Guyana.

Of

these

84%

were

Hindus,

but

16%

were

Sunni

Muslims.'(n3)

There

has

also

been

a

Shia

and

later

an

Ahmadiyya

presence

in

Guyana.

However,

their

numbers

are

minuscule

and

too

insignificant

to

cause

any

friction.

Immigration

records

indicate

that

the

majority

of

Muslims

who

migrated

to

Guyana

and

Suriname

came

from

the

urban

centres

of

Uttar

Pradesh,

Lucknow,

Agra,

Fyzabad,

Ghazipur,

Rampur,

Basti

and

Sultanpur.

Small

batches

also

came

from

Karachi

in

Sind,

Lahore,

Multan

and

Rawalpindi

in

the

Punjab,

Hyderabad,

in

the

Deccan,

Srinagar

in

Kashmir,

and

Peshawar

and

Mardan

in

the

Northwest

Frontier

(Afghan

areas).

Immigration

certificates

reveals

major

details

of

Muslim

migrants.

Their

origins

such

as

District

and

villages,

colour,

height,

and

caste

are

all

indicated.

Under

caste

Muslims

are

identified

as

Musulman,

Mosulman,

Musulman,

Musalman,

Sheik

Musulman,

Mahomedaan,

Sheik,

Jolaba,

Pattian,

(Pathan),

and

Musulman

(Pathan).

Religion

and

caste

identified

many

Muslims.

From

looking

at

their

district

of

origin

one

can

tell

of

their

ethnicity,

whether

they

were

Sindis,

Biharis,

Punjabi,

Pathans

or

Kashmiri.

Their

physical

profile

on

the

Immigration

Certificate

also

help

in

recognizing

their

ethnicity.

There

are

enormous

spelling

mistakes

on

the

Immigration

Certificates.

Musulman,

the

Urdu

world

for

Muslim

is

spelled

many

different

ways

and

sometimes

Muslims

were

referred

to

as

Mahomedaan.

Districts,

Police

Depot

and

villages

are

frequently

misspelled,

for

example

Peshawar

is

spelled

Peshaur

and

Nowsherra

is

Nachera,

among

many

others.

The

Afghan

Pathan

clan

also

were

among

the

indentured

immigrants.

Immigration

Certificates

clearly

indicate

under

the

category

of

"caste"

Pathans,

Pattan,

Pattian

or "Musulman

Pathan."

The

fact

there

were

Pathans

settlements

in

northern

India,

explains

this

migration.

Also

as

indicated

by

Immigration

Certificates,

Pathans

migrated

from

the

Northwest

Frontier

and

Kashmir.

One

of

Guyana's

oldest

Mosques,

the

Queenstown

Jama

Masjid,

was

founded

by

the

Afghan

community,

which

had

apparently

arrived

in

this

country

via

India.

(n4)

Afghan

and

Indian

Muslims

living

in

this

area

laid

the

foundation

for

the

Masjid.

Thus

according

to

several

accounts,(n5)

there

were

educated

Muslims

among

these

early

arrivals.

One

Imam

reports

there

were

two

hafizul

Qur'an

who

were

`residing

in

Clonbrook,

East

Coast

Damerara,

bearing

the

last

name

Khan'.(n6)

The

South

Asian

Connection

The

history

of

Guyanese

Muslims

is

directly

linked

to

the

Indian

subcontinent,

but

it

is a

history

that

has

been

ignored

by

Caribbean

scholars

of

East

Indian

history.

One

aspect

of

this

history

that

has

drawn

much

debate

among

the

different

scholars

and

Islamic

organizations

in

Guyana

is

the

`

Indo-Iranian'

connection.

When

this

term

is

used

in

this

article

it

refers

to

the

linguistic

and

cultural

aspects

that

the

Guyanese

Muslims

inherited

from

West

and

South

Asia

(Iran,

Afghanistan,

Pakistan,

India

and

Central

Asia).

Iran

and

Central

Asia

played

a

key

role

in

the

history

and

civilization

of

South

Asian

Muslims.

The

spread

of

Islam

to

India

is

attributed

to

the

Central

Asian

Turks

who

adopted

Persian

as

the

official

language

of

the

Mughal

Court

in

India.

If

Islam

did

not

travel

to

the

subcontinent

it

would

have

never

had

such

an

impact

in

Guyana,

Suriname

and

Trinidad.

Persianized

Central

Asian

Turks

under

the

leadership

of

Muhammad

Zahiruddin

Babur

established

the

Mughal

dynasty

and

brought

cultural

ambassadors

from

Iran,

Turkey

and

Central

Asia

to

India.

|

Today in Guyana there is much controversy as to the cultural aspects that Muslims brought from the subcontinent beginning with their migration in the year 1838. There exist two camps in Guyana, one comprising the younger generation who prefer to get rid of the `Indo-Iranian' heritage, and the other the older generation who would like to preserve this tradition. Some link this tradition to Hinduism and a continuous attempt is being made to purge `cultural Islam' of `un-Islamic' innovations (bida'). Van der Veer notes that these forms, brought by the indentured immigrants to the Caribbean, were heavily influenced by the cultural patterns of the subcontinent, as opposed to those of the Middle East.(n7) Aeysha Khan quotes Samaroo: `in modern day Trinidad and Guyana, where there are substantial Muslim populations, there is much confusion, often conflict, between the two types of Islam'.(n8) In Guyana today the younger generation who have studied in the Arabic-speaking world prefer Arabic over Urdu and view South Asian traditions as un-Islamic. In the subcontinent Urdu helps to define a South Asian Muslim. In fact, Urdu and Islam for South Asian Muslims define one's cultural identities. |

The

Language:

Urdu

Urdu,

a

common

language

developed

in

the

Indian

subcontinent

as a

result

of a

cultural

and

linguistic

synthesis,

was

brought

to

Guyana

by

South

Asian

Muslims

from

the

subcontinent

where

its

history

goes

further.

After

the

Mughal

invasion

of

India,

the

mingling

of

Arabic,

Turkic,

Persian

and

Sanskrit

languages

developed

into

a

new

`camp'

language

called

Urdu.

The

word

`Ordu'

or

Urdu,

which

is

Turkish

in

origin,

means

`camp'

and

is

mostly

associated

with

an

army

camp.

It

was

towards

the

end

of

the

Mughal

rule

in

India

that

Urdu

language

was

given

a

national

status.

The

language

was

nurtured

at

three

centres

in

India:

the

Deccan,

Delhi

and

Lucknow.

Once

Urdu

was

adopted

as

the

medium

of

literary

expression

by

the

writers

in

these

metropolises,

its

development

was

rapid,

and

it

soon

replaced

Persian

as

the

court

language

and

principal

language

of

Muslim

India.(n9)

However,

in

the

1930s

Urdu

suffered

reverses

with

the

resurgence

of

Hindu

nationalism

in

India.

A

new

people's

language

was

developed

replacing

the

Persian

script

with

the

Devangari

script

and

it

was

called

Hindi.

|

Urdu, distinguished from Hindi by its Persian script and vocabulary, is today the national language of Pakistan and one of the official languages of India. It is one of the most popular spoken languages of South Asia, and has acquired a wide distribution in other parts of the world, notably the UK, where it is regarded as the major cultural language by most subcontinent Muslims. In Guyana today, Urdu is popular among the Indo-Guyanese who watch films and listen to music from the Bombay film industry. Contributing to its role as the chief vehicle of Muslim culture in South Asia is its important secular literature and poetry, which is closely based on Persian models. However, Urdu is taking a backstage in Guyana due to English language proliferation and the Muslim orthodox movement leading to a focus on Arabic.

Only one Islamic organization in Guyana today, the United Sad'r Islamic Anjuman (which is also the oldest surviving Islamic organization in Guyana), offers Urdu in its instructional programme for teaching the qasida (hymns that sing praises to God and the Prophet). |

They

regularly

hold

qasida

competitions

throughout

the

country

and

award

prizes

to

encourage

participation.

Qasida

is

part

of

the

`Indo-Iranian'

legacy.

It

is

an

attempt

by

the

Anjuman

to

preserve

the

uniqueness

of

Guyana's

Muslim

heritage.

Though

the

students

were

generally

told

that

they

were

learning

Arabic,

it

was

Urdu

that

was

being

taught.

Having

migrated

to

New

York,

an

ustad

(teacher)

from

a

village

in

Guyana

remarked

to

the

author

`the

Arabic

here

is

different

than

that

which

I

was

teaching

at

the

madrasah

in

Guyana'.

Little

did

he

realize

that

it

was

Urdu

and

not

Arabic

that

he

was

teaching

back

in

Guyana.

Some

are

embarrassed

to

say

that

they

were

teaching

Urdu

while

calling

it

Arabic.

This

is

one

of

many

stories

that

echo

throughout

Guyana.

One

remembers

hearing

the

so

called

Arabic

alphabet:

`alif,

be,

pe,

se,

jim

che,

he...

zabar',

and

`pesh

'.

In

Arabic

there

is

no `pe',

`che',

`zabar',

and

`pesh'.

After

familiarizing

oneself

with

Urdu,

one

realizes

that

it

was

Urdu

that

was

being

taught

in

Guyana.

Ahmad

Khan

a

trustee

of

the

Queenstown

Jama

Masjid

says

that

for

most

Guyanese

Muslims

their

mother

tongue

was

Urdu.(n10)

However,

by

1950

Urdu

started

fading

with

the

introduction

of

Islamic

texts

in

English

and

it

has

now

almost

disappeared.(n11)

According

to

Pat

Dial,

a

Guyanese

historian,

during

the

early

twentieth

century

Urdu

and

Arabic

were

taught

in

the

madrasah

annex

of

the

Jama

Masjid

and

the

young

were

introduced

to

the

Namaz.

In

those

early

years,

far

more

people

spoke

Urdu

than

English.(n12)

|

|

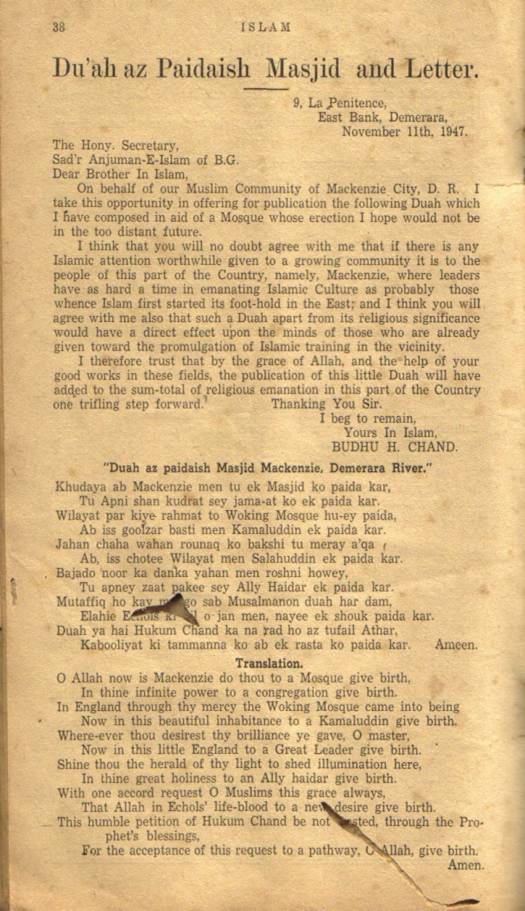

Urdu dua composed seeking Divine intervention for the construction of Masjid, in Mackenzie, Guyana, 1947 |

Some Questionable Traditions

In any civilization, there is cultural synthesis. The usage of Urdu is by no means related to Hinduism. Even though it is indigenous to the subcontinent it remains a legacy of the Muslim period. Other aspects of this heritage include the tradition of qasidas, tazim-o-tawqir, milaad-sharief, the dua and the nikkah, all performed in Urdu. In Guyana, as in Trinidad, as well as in other countries in the Caribbean, Muslims are saying the fatiha over food, celebrating the Prophet's birthday (milad-un-nabi) and ascension (miraj) and singing qasida, all in Urdu.(n13) However, the debate over these very rituals has created deep frictions among Guyanese Muslims. Similar traditions are prevalent in the subcontinent, as well as in Central Asia, the Caucasus region, Turkey, Iran and other Islamic lands. The different Sufi orders that were responsible for the spread of Islam in many parts of the world had patronized these traditions. Their orthodoxy or unorthodoxy has become the subject of major debates everywhere. We shall review below some of these `questionable' traditions.

Tazim-o-tawqir

The Urdu term tazim is well known among Guyanese Muslims and it constitutes an established practice inherited from their forefathers. However, if one asks what is the meaning of the word tazim, one gets many different answers. But if one asks what is tazim, they will say it is the standing and reciting of `ya nabi salaam aleika, ya rasul salaam aleika, ya habib salaam aleika...' However, tazim is much more than standing and reciting thanks and praises to the Prophet. It is about respect, honour and reverence.

Supporters of tazim-o-tawqir say that it is essential for every believing Muslim, to practice tazim-o-tawqir but within a frame work that it does not become an evil bida'. Tazim has all along been observed in Guyana, but today there is much controversy over this practice. The educated person who is knowledgeable of Islam sees this practice as un-Islamic. Most others see no problem with it and continue with its practice. Still others see the practice as bida'-e-hasanah or a good innovation.

|

Three

maulanas

from

the

subcontinent

who

are

highly

regarded

in

Guyana,

Suriname

and

Trinidad

have

all

endorsed

this

practice.

Their

support

of

tazim

carries

heavy

weight

because

of

their

piety,

education

and

unselfish

dedication

to

the

upliftment

of

Muslims.

Maulana

Noorani

Siddique

has

called

upon

those

who

oppose

tazim

to

provide

the

proof

why

it

should

not

be

practised.

He

has

challenged

the

critics

that

tazim

is

in

accordance

with

the

Sunni

Hanafi

madhab

and

is

not

in

conflict

with

the

Qur'an

and

the

Sunnah.

|

Milad-un-nabi

Supporters of milad-un-nabi say that the celebration is the commemoration and observance of the birth, life, achievements and favours for the Prophet. Many Sufi orders such as the Chishtiyah and Naqshbandiyah support this celebration. They say that expressions of love of the Prophet by the ummah in the form of milad-un-nabi is a humble effort by the ummah to show gratitude to Allah for His favour of blessing man with such a nabi (Prophet), and to the Nabi for bringing man out of the darkness of ignorance (jahiliyah). The essence of milad-un-nabi is to remember and observe, discuss and recite the event of the birth and the advent of the Prophet.(n14) Many argue that these practices are all in keeping with Qur'anic directives and assert that great ulema-e-haqq such as Ibn Hajar Haitami Hafiz, Ibn Hajar Asqalani, Ibn Jawzi, Imam Sakhaawi, and Imam Sayyuti have regarded milaad-un-nabi as mustahab (good deed).(n15)

|

Opponents

of

milad-un-nabi

have

called

this

practice

a

bida'

or

an

innovation.

Some

argue

that

there

are

two

types

of

bida':

bida-e-hasanah

and

bida'-e-sayiah

(good

innovations

and

evil

innovations).

Proponents

argue,

`if

the

objection

is

to

the

current

information

[sic]

that

the

observance

of

milad-un-nabi

takes,

and

is

thus

regarded

as

an

evil

bida',

then

there

are

many

other

bida'

which

came

about

after

the

era

of

the

tabii

taabioon

as

well,

which

given

the

requirements

of

the

era

were

necessary.(n16)

They

argue

that

following

this

logic

the

compilation

and

classification

of

Hadith

is

also

a

bida'

which

originated

after

the

era

of

the

sahaaba,

taabioon

and

tabie

taabioon

(quroon-e-thalaatah).

`The

current

form

of

Hadith

is

also

an

innovation.

Books

of

Hadith,

principles

of

Hadith,

principles

of

jurisprudence,

the

schools

of

fiqh

are

all

bida'

and

innovations

which

originated

two

centuries

or

more

later'.(n17)

However,

they

agreed

that

these

are

good

bida'

from

which

the

ummah

has

benefited

greatly.

In

discussing

the

survival

of

Islam

in

Guyana,

Hamid

says,

`They

were

able

to

do

this

(maintain

Islam)

through

Qur'anic

and

milaad

functions,

and

other

regular

social

interactions,

in

spite

of

distance

and

the

demands

of

indentured

ships'.(n18)

In

arguing

for

the

legitimacy

of

milad-un-nabi,

M.

W.

Ismail

refers

to

several

Islamic

scholars

who

have

agreed

that

milad-un-nabi

is a

good

bida'

or

bida'

hassanah.

He

quotes

the

following

from

Imam

Ibn

Hajar

Al-Asqalani

who

in

explaining

Sahih

Bukhari

says:

`Every

action

which

was

not

in

practice

at

the

Prophet's

time

is

called

or

known

as

innovation,

however,

there

are

those

which

are

classified

as

good

and

there

are

those

which

are

contrary

to

that'.(n19)

Ismail

then

made

reference

to

Fatmid

Egypt

(909-1171

AD)

and

quoted

Imam

Ibn

Kathir

from

his

book,

Al-Bidaya

(Vol.

13,

p.

136):

`Sultan

Muzafar

used

to

arrange

the

celebration

of

melaad

sharief

with

honour,

glory,

dignity

and

grandeur.

In

this

connection

he

used

to

arrange

a

magnificent

festival'.(n20)

Imam

Kathir

continued,

`He

was

a

pure

hearted,

grave

and

wise

aalim

and

a

just

ruler,

may

Allah

shower

his

mercy

upon

him

and

grant

him

an

exalted

status'.(n21)

In

trying

to

prove

the

validity

of

milad-un-nabi,

the

Sheikh

quoted

Al-Hafiz

Ibn

Hajar

who

when

asked

about

the

celebration

said,

`

meelad

shareef

is,

in

fact,

an

innovation

which

was

not

transmitted

from

any

pious

predecessor

in

the

first

three

centuries.

Nevertheless,

both

acts

of

virtue

as

well

as

acts

of

abomination

are

found

in

it'.(n22)

Opponents

argue

that

the

Prophet

Muhammad

(SWS)

said,

`Whoever

brings

forth

an

innovation

into

our

religion

which

is

not

part

of

it,

it

is

rejected'.(n23)

They

further

quote

the

Prophet:

`Beware

of

inventive

matters

for

every

invention

is

an

innovation

and

every

innovation

is

evil'.(n24)

Supporters

respond

that

those

who

quote

these

two

Hadiths

and

claim

that

all

innovation

is

bida'

and

reprehensible

have

in

fact

accused

Muslim

learned

men,

including

the

Caliph

Umer,

of

committing

`evil'

innovations.(n25)

This

would

include

many

other

`innovations'

which

are

widely

accepted

and

practised

by

Muslims

today

such

as

the

tarawih

prayers,

the

introduction

of

the

second

adhan

during

Friday's

congregational

prayers,

the

introduction

of

reading

`bismillah

al-rahman

al-rahim

before

commencing

tashahud,

and

sending

praise

and

salaams

upon

the

Prophet.

The

Anjuman

Hifazatul

Islam

and

the

West

Demerara

Muslim

Youth

Organization

have

recently

been

in

the

forefront

promoting

Milad-un-Nabi

,

Meraj-un-Nabi

and

Muharram

programmes.

The

Muslim

Journal,

the

voice

of

the

Anjuman

Hifazatul

Islam

and

the

West

Demerara

Muslim

Youth

Organization,

express

concern

that

consorted

efforts

have

been

made

to

eradicate

Milad-un-Nabi

observation

in

Guyana.

"For

over

twenty

years,

continuos

efforts

have

been

made

to

destroy

Milad

programmes

from

our

community,

and

after

all

these

efforts

and

years,

two

thousand

persons

have

still

turned

out

to

support

qaseeda"

(1999,

p.

2).

The

Qasida

The

qasida

(hymn

of

praise)

has

always

been

a

part

of

the

Arab

tradition,

and

it

spread

from

the

heart

of

Arabia

to

the

Islamic

periphery.

Arabic

language

impacted

heavily

on

the

vocabulary,

the

grammar

and

the

literary

prose

of

other

languages

such

as

Persian,

Urdu,

Turkish,

Bosniak,

Hausa

and

Swahili

among

others.

Its

contribution

to

the

literature

of

these

languages

helped

their

revival.

Today

qasidas

are

written

in

Arabic

but

also

in

other

languages

spoken

by

Muslims

and

have

become

a

part

of

the

Islamic

cultural

expression.

There

are

four

types

of

qasida,

which

are

characterized

according

to

their

evolution.

The

pre-Islamic

qasida,

rooted

in

the

ancient

Arab

tribal

code;

the

panegyric

qasida,

expressing

an

ideal

vision

of a

just

Islamic

government;

the

religious

qasida,

exhorting

different

types

of

commendable

religious

conduct;

and

the

modern

qasida,

influenced

by

secular,

nationalist,

or

humanist

ideals.

These

many

varieties

of

qasida

greatly

influenced

the

development

of

public

discourse

in

many

Muslim

countries.

Guyanese

Muslims

have

only

been

exposed

to

religious

qasidas.

However,

in

Guyana

today

there

is

no

formal

school

of

qasida

teaching.

What

Guyanese

Muslims

know

about

qasida

is

what

has

been

handed

down

from

one

generation

to

another.

It

is

not

a

written

tradition,

but

rather

an

oral

one

which

inevitably

has

lost

its

scholarly

character.

No

one

today

learns

the

prose

and

the

grammar

of

qasida

and

there

is

no

one

to

question

nor

to

maintain

the

standard

of

good

qasida.

Madrasahs

do

not

teach

qasida,

but

a

few

Islamic

organizations

in

Guyana

do

hold

qasida

competitions.

The

question

remains,

who

sets

the

standards

for

winning

and

what

are

the

criteria

for

winning?

This

aspect

of

cultural

Islam

no

doubt

has

been

influenced

by

the

host

environment.

Today

in

Guyana

there

is a

movement

among

a

handful

to

resurrect

this

tradition.

However,

the

lack

of

enthusiasm

from

the

younger

generation,

many

of

whom

have

studied

in

the

Arab

world,

compounded

with

its

questionable

Islamic

legitimacy,

will

soon

make

these

traditions

extinct.

In

1999

the

Anjuman

Hifazatul

Islam,

the

Muslim

Youth

League,

and

the

Sadr

Islamic

Anjuman

in

conjunction

with

the

CIOG

held

a

national

qaseeda

competition.

County

level

compition

was

held

in

Berbice,

Essequibo

and

Demerara.

In

its

editorial,

the

Muslim

Journal

writes,

"then

it

was

announced

on

television

that

Qaseeda

and

Mowlood

is

an

"Indian"

something

and

therefore

has

nothing

to

do

with

Islam."

(1999,

p.2).

With

two

thousand

people

attending

the

final

Qaseeda

competition,

the

Journal

writes,

"

The

people

have

spoken,

and

no

Shaikh,

Maulana,

Qari,

Hafiz

or

self

proclaimed

Islamic

scholars

can

deny

the

voice

of

the

people"

(2).

The

visits

of

several

Maulanas

to

the

Caribbean,

notably

Maulana

Fazlur

Rahman

Ansari,

Maulana

Abdul

Aleem

Siddique

and

his

son

Maulana

Ahmad

Shah

Noorani

Siddique,

provided

opportunity

to

the

Guyanese

Muslims

to

seek

clarification

from

these

scholars

of

the

Hanafi

madhab

regarding

the

practice

of

tazim,

milad-un-nabi

and

qasida.

These

scholars

endorsed

these

practices

and

refuted

claims

that

these

are

evil

innovations.

They

were

able

to

convince

the

locals

that

based

on

the

Qur'an,

Hadith

and

the

fiqh,

tazim,

milad-un-nabi

and

qasida

were

within

the

parameters

of

Islam,

and

if

kept

within

the

boundaries

of

Islam

these

practices

are

good

bida'.

Arabization

and

the

Sunnification

Process

Before

the

1960s,

Muslim

missionaries

who

visited

Guyana

came

almost

exclusively

from

the

Indian

subcontinent

and

visited

frequently.

This

influx

of

missionaries

and

the

Islamic

literature

they

brought

with

them

helped

to

promote

and

maintain

the

Sunni

Hanafi

madhab.

It

was

not

until

the

1960s

that

Guyanese

Muslims

made

contacts

with

the

Arabic-speaking

world.

After

Guyana's

independence

in

1966,

the

younger

generation

of

Muslims

were

keen

to

make

these

contacts.

Guyana

established

diplomatic

relations

with

many

Arab

countries.

Egypt,

Iraq

and

Libya

opened

embassies

in

Georgetown,

the

capital

of

Guyana.

Many

Muslim

youths

went

to

Saudi

Arabia,

Egypt

and

Libya

to

study

Islamic

theology

and

the

Arabic

language.

Eventually

Arabic-speaking

Muslims

began

to

take

an

interest

in

Guyana

and

many

travelled

there

to

render

assistance

to

their

Muslim

brethren.

In

1977

Libyan

Charge

d'Affaire

Mr

Ahmad

Ibrahim

Ehwass

arrived

in

Guyana.

He

introduced

many

activities

to

benefit

the

Muslim

community,

especially

the

youth.

Many

scholarships

were

given

to

young

Guyanese

Muslims

to

study

in

Libya,

and

in

1978

he

was

responsible

for

the

formation

of

the

Guyana

Islamic

Trust

(GIT).

In

1996

the

late

President

Cheddi

Jagan

of

Guyana

toured

several

Middle

Eastern

countries

and

appointed

a

Middle

Eastern

envoy.

His

official

visits

took

him

to

Syria,

Kuwait,

Bahrain,

Qatar,

the

United

Arab

Emirates

and

Lebanon.

The

1979

Islamic

Revolution

of

Iran

marked

a

new

beginning

of

Guyana/Iranian

relationship.

Guyana

and

Iran

established

diplomatic

relationship

in

the

80's

and

through

various

multilateral

organization

such

as

the

UN,

the

Group

of

77,

the

Non-Aligned

Movement,

and

the

OIC

cooperated

on

various

issues.

Iran

appoints

a

non-resident

ambassador

to

Guyana,

who

is

based

in

Caracas.

With

the

Islamic

Republic

severing

ties

with

Israel

and

South

Africa

in

1979,

relationship

with

Guyana

improved

tremendously.

Guyana

and

Iran

among

other

developing

nations

fought

against

the

racist

regimes

in

Israel

and

South

Africa.

Guyana

like

Iran

at

the

UN,

voted

for

General

Assembly

Resolution

branding

Zionism

as

racism.

Dr.

Cheddi

Jagan

and

the

Iranian

Foreign

Minister

Mr.

Ali

Akbar

Velayati

held

a

bilateral

meeting

in

Colombia

on

18th

of

October

1995,

during

the

Non-

Aligned

Summit.

Jagan

said,

"The

Islamic

Republic

of

Iran

has

made

significant

gains

in

many

areas

and

we

are

interested

in

having

close

cooperation

with

Iran

at

International

forums."

(Iranian

News

Agency).

Dr.

Jagan

extended

an

invitation

to

the

Iranian

Foreign

Minister

to

visit

Georgetown.

In

July

of

1997,

Special

Envoy

and

Deputy

Minister

of

Foreign

Affairs

of

Iran,

Mr.

Mahmood

Vaezi

visited

Guyana.

Guyana

in

December

of

1997

attended

the

OIC

heads

of

government

summit

in

Teheran.

In

July

of

2000

an

Iranian

trade

fair

and

exhibition

was

held

in

Georgetown.

The

exhibition

was

meant

to

acquaint

Guyanese

with

Iranian

goods,

while

the

Iranians

examined

local

items

for

export,

and

it

was

intended

to

encourage

Iranian-Guyanese

joint

ventures.

It

was

also

in

1996

that

Guyana

officially

became

a

permanent

observer

in

the

Organization

of

Islamic

Conference

(OIC).

This

further

strengthened

Guyana's

ties

with

the

Middle

East,

coupled

with

its

traditional

support

for

a

Palestinian

homeland.

In

1997,

during

the

8th

Summit

of

the

OIC

in

Teheran,

Iran,

Dr

Mohammed

Ali

Odeen

Ishmael,

Guyana's

Ambassador

to

Washington,

represented

Guyana.

Guyana's

application

for

permanent

membership

in

the

OIC

was

accepted

in

1998

and

Guyana

became

the

56th

member

state

of

the

OIC

that

year.

Minister

of

Foreign

Affairs,

Clement

Rohee

was

head

of

the

Guyanese

delegation

to

the

OIC

heads

of

government

summit

in

Doha,

Qatar

in

2000.

Dr.

Ishmael

was

a

member

of

the

Doha

delegation

as

well.

The

Ambassador

has

attended

all

OIC

Heads

of

States

Summit

and

Foreign

Minister

Summit

since

Guyana's

membership.

In

June

of

1999

Ambassador

Odeen

Ishmael

led

Guyana's

delegation

to

the

twenty-sixth

session

of

the

Islamic

Conference

of

Foreign

Ministers

in

Ougadougou,

Burkina

Faso.

Dr.

Odeen

Ishmael

was

also

head

of

the

Guyanese

delegation

in

June

of

2000

at

the

27th

session

of

the

Islamic

Conference

of

Foreign

Ministers

in

Kuala

Lumpur,

Malaysia.

Most

recently,

in

June

of

2001,

the

Washington

based

diplomat

was

once

again

head

of

the

delegation

of

Guyana

to

the

28th

Session

of

the

Islamic

Conference

of

Foreign

Ministers

in

Bamako,

Mali.

He

is

indeed

the

unofficial

ambassador

of

Guyana

to

the

OIC.

At

the

Bamako

Conference

Guyana

made

a

call

for

international

observers

in

Palestine.

The

Palestinian

delegation

in

Mali

was

very

pleased

with

Guyana's

call

for

international

observers,

and

actually

the

Guyanese

delegation

was

the

only

delegation

that

made

this

demand.

In

his

speech,

Odeen

Ishmael

said,

"In

this

regard,

effective

mechanisms

must

be

identified

to

implement

the

relevant

proposals

aimed

at

achieving

a

lasting

settlement

to

the

situation.

Guyana

supports

the

call

for

international

observers

to

be

positioned

in

Palestinian

territory

to

monitor

the

situation"

(www.guyana.org).

The

ambassador

has

represented

Guyana's

interest

in

this

organization

and

has

helped

forged

stronger

ties

with

Islamic

nations.

He

is

very

familiar

with

member

states

and

the

politics

of

the

organization.

At

the

OIC

and

at

the

UN

Guyana

continue

to

champion

the

fight

for

a

Palestinian

homeland.

Guyana

also

supports

UN

Security

Council

Resolutions

242

and

338,

and

has

called

on

Israel

to

implement

them.

At

the

Doha

Summit,

Chairman

Arafat

held

discussion

with

Ambassador

Odeen

Ishmael.

The

Chairman

acknowledged

Guyana's

continued

support

towards

the

Palestinian

cause.

However,

Guyanese

Muslims

returning

from

the

Arab

world

to

Guyana

began

introducing

changes

that

irked

the

local

Muslims.

They

advocated

changes

that

they

believed

were

more

authentic

to

Islam

as

well

as

to

the

Arab

world.

Many

who

studied

in

Arabia

were

highly

influenced

by

Wahabism,

and

thus

a

new

interpretation

of

Islam

was

brought

to

Guyana

which

confused

the

locals.

Wahabism's

interpretation

of

Islam

came

in

conflict

with

some

aspects

of

the

Muslim

culture

of

the

subcontinent.(n26)

One

scholar

notes

that

the

`Guyanese

have

not

really

benefited

from

the

scholarships

granted

to

students

to

study

in

Arabia,

India

or

Pakistan

because

only

a

few

have

returned

home,

and

even

of

the

few

who

have

returned

home,

an

even

lesser

number

have

made

positive

contributions.

Some

have

needlessly

raised

juristic

issues

which

serve

only

to

create

division

and

confusion

in

the

community'.(n27)

In

the

1970s

Guyanese

Muslims

began

a

movement

toward

greater

homogenization

and

uniformity.

Greater

orthodoxy

or

sunnification

accompanied

this

tendency

toward

uniformity.

Sunnification

means

the

abandonment

of

local

and

sectarian

practices

in

favour

of a

uniform

orthodox

practice.

The

position

of

Muslims

as a

minority

group

in

Guyana

has

assisted

this

process

but

the

emergence

of

Muslim

countries

and

the

work

of

Muslim

missionaries

who

have

visited

Guyana

have

also

aided

it.

The

establishment

of

Muslim

colleges

to

train

imams

and

the

generosity

of

Muslim

governments

to

provide

scholarships

for

young

Muslim

Guyanese

have

been

helping

to

produce

a

uniform

orthodox

practice.

In

essence,

denying

one's

Indian-ness

helps

to

bring

one

closer

to

the

`Arab-ness'

of

Islam.

Arabic

and

Arab-ness,

it

would

seem

today

in

Guyana,

legitimizes

Islam,

and

South

Asian

`cultural

Islam'

is

now

viewed

as

un-Islamic

and

polluted

with

innovations.

As

in

Mauritius,

Suriname,

Trinidad

and

Tobago,

the

process

of

sunnification

in

Guyana

took

place

under

political

competition

between

Hindus

and

Muslims.

This

process

of

Islamization

or

the

revivalist

movement,

whose

impact

has

been

felt

since

the

1979

Iranian-Islamic

revolution,

is

an

expression

of a

need

for

a

separate

identity.

In

many

of

these

countries

Hindus

and

Muslims

have

had

an

antagonistic

relationship.

The

revivalist

movement

is

an

expression

of

political

dominance.

Muslims

refused

to

be

dominated

by

Christians

or

Hindus

in

Guyana.

Some

Muslims

in

Guyana

have

entertained

the

idea

of

forming

a

Muslim

political

party

for

some

time.

This

indeed

happened

in

the

1970s

with

the

formation

of

the

Guyana

United

Muslim

Party

(GUMP)

by

Ghanie.

The

party

founder

was

hoping

to

capture

five

seats

in

the

Parliament.

But

he

was

unsuccessful

in

rallying

the

Muslim

vote.

Guyana's

two

main

political

parties

have

always

courted

the

Muslims.

Nevertheless,

most

Guyanese

Muslims

today

believe

that

aligning

themselves

with

political

parties

does

them

no

good.

The

tendency

toward

orthodoxy

seems

to

have

affected

local

religious

practices,

as

seen

in

the

gradual

disappearance

of

the

observance

of

Muharram,

which

is

associated

with

the

Shia

Muslim

tradition.

The

tazia

or

the

tadjah

(a

procession

of

mourners

marking

the

anniversary

of

the

assassination

of

Hussein,

the

grandson

of

the

Prophet)

was

an

annual

event

in

which

Muslims

as

well

as

non-Muslims

participated.

However,

orthodox

Muslims

in

Guyana

began

to

see

the

celebration

of

tazia

as

un-Islamic.

Some

agreed

that

it

was

just

a

time

to

congregate

for

the

sake

of

socializing.

Hindus,

it

seems,

also

participated

in

this

festival

which

later

came

under

heavy

criticism

from

pious

Muslims

of

the

Hanafi

madhab.

According

to

Basdeo

Mangru,

there

was

hardly

any

evidence

of

conflict

between

the

Hindus

and

Muslims

to

suggest

a

lack

of

social

cohesion

which

had

prevailed

between

the

Africans

and

the

Creoles

under

slavery.(n28)

However,

pressures

increased

from

many

sources

to

end

this

practice.

Muslims

wanted

the

state

authorities

to

recognize

the

more

orthodox

holidays

such

as

the

two

Eids

and

Youman-Nabi.

By

1996,

when

Guyana

achieved

independence,

the

taziya

was

history.

Today

Muslim

leaders

are

constantly

stressing

orthodoxy.

Religious

personalities

both

in

Guyana

and

those

returning

from

overseas

preach

strongly

against

what

are

considered

un-Islamic

practices.

There

are

many

disputes

between

orthodox

and

traditionalists

in

which

the

former

accuse

the

latter

of

pagan

practices.

This

is

in

contrast

to

the

earlier

period

when,

as

one

scholar

notes,

`Guyana

did

not

experience

any

major

juristic

problems

within

the

period

1838-1920s.

At

no

time

were

there

more

than

750

Shia

and

by

1950

they

seemed

to

have

been

absorbed

into

the

Sunni

Muslim

group'.(n29)

However,

after

the

Iranian

revolution

of

1979

and

with

the

coming

to

power

of

Imam

Khomeini

in

Iran,

there

was

a

sudden

upsurge

of

Shiism

across

the

world.

Soon

thereafter

following

the

arrival

of a

Shia

missionary

in

Guyana,

two

groups

were

established,

one

in

Linden,

Demerara

and

another

in

Canje,

Berbice.

During

Muharram

in

1994

a

Shia

organization,

the

Bilal

Muslim

Mission

of

North

America

sent

a

couple

of

people

to

visit

Guyana.

Shia

Muslims

feel

resented

by

the

main

Muslim

body

merely

because

of

Wahhabis

"propaganda".

Since

then

BMMA

has

been

paying

regular

visits

to

Trinidad

and

Guyana.

BMMA

sent

hundreds

of

copies

of

Quran

translated

by

S.V.

Mir

Ahmad

Ali

and

other

literature.

BMMA

also

supplied

the

small

community

in

Trinidad

and

Guyana

with

TV,

VCR,

computer,

printer

and

fax

machines.

BMMA

also

financially

supports

the

running

of

Madressah

in

Guyana

and

dispatches

reading

material

and

other

literature

on

regular

basis.

However,

the

impact

of

Shiism

in

Guyana

is

yet

to

be

determined.

Beginning

in

the

1970s,

the

Guyanese

Muslims

who

returned

from

Arab

educational

institutions

began

a

process

of

reconstructing

the

past.

They

tried

to

de-emphasize

their

Indian

cultural

heritage

by

reconstructing

or

redefining

their

history.

Much

of

it

was

an

effort

to

distinguish

themselves

from

the

Hindus

in

order

to

promote

a

separate

Muslim

identity.

Although

the

majority

are

descendants

of

South

Asian

indentured

labourers,

they

presented

themselves

as

descendants

of

Arabs.

While

their

mother

tongue

was

Urdu,

many

claimed

that

it

was

Arabic.

During

the

mid-1970s

a

powerful

Arabization

movement

had

emerged,

and

it

became

more

attractive

for

the

orthodox

Muslims

in

Guyana

to

be

part

of

this

movement

than

to

trace

one's

roots

in

Pakistan

or

India.

This

movement

to

create

a

purer

Islamic

identity

was

contested

by

other

traditionalists,

especially

the

older

generation.

Today

in

Guyana

many

Muslims

are

concerned

with

the

spread

of

other

madhahib.

The

Director

of

Education

and

Dawah

of

the

CIOG,

Ahmad

Hamid

says,

`As

from

1977,

Muslims

in

Guyana

saw

the

introduction

of

the

teaching

of

other

madhahibs.

These

were

new

to

the

local

Muslims

and

created

some

serious

problems'.(n30)

A

trustee

of

the

Queenstown

Jama

Masjid,

Ayube

Khan,

is

also

concerned

about

this

division

and

regretted

that

too

many

dissentions

have

occurred

`because

of

infiltration

of

disruptive

elements'.(n31)

This

same

concern

was

raised

by

the

Imam

of

the

Queenstown

Jama

Masjid,

Haji

Shaheed

Mohammed,

who

says

that

`

With

petty

misunderstandings,

the

exuberance

of

the

youths

and

the

need

for

general

guidance

to

see

that

the

Jamaat

remains

on

the

Hanafi

madhab,

being

Imam

of

the

Queenstown

Jama

Masjid

can

be a

trying

task'.(n32)

The

shift

from

Urdu

to

Arabic

and

the

emphasis

to

do

away

with

traditional

practices

illustrates

the

attempts

to

emphasize

cultural

identity.

They

link

these

practices

to

Hinduism,

hence,

would

like

to

purge

Islam

of

these

`innovations'.

The

association

of

Arabic

with

Muslims

is

new

in

Guyana

and

the

demand

for

Arabic

illustrates

the

emphasis

to

differentiate

from

the

Hindus.

Muslim

children

are

taught

Arabic

and

Urdu

during

the

evening

at

Muslim

schools

(madrasah).

These

languages

are

restricted

to

religious

contexts

because

all

Guyanese

Muslims

speak

English.

There

has

been

a

movement

recently

in

Guyana

to

introduce

Hindi

into

the

national

curriculum.

If

this

becomes

a

reality

Muslims

will

demand

Arabic

or

Urdu

as

well.

A

Hindu

dominated

government

in

Guyana

will

create

tension

with

the

Muslims.

Muslims

in

Guyana

are

concerned

with

safeguarding

the

interests

of

their

own

community.

They

are

better

organized

than

the

Hindus.

Muslim

religious

associations

and

mutual

aid

societies

support

those

in

the

community

who

need

help.

The

mosque

constitutes

the

focal

point

of

the

local

Muslim

community

and

Islamic

teachings

at

the

mosque

and

the

vernacular

schools

aid

in

the

adherence

to

Islam

and

its

precepts.

Guyanese

Muslims

are

an

endogamous

group;

kinship

and

marriage

bonds

further

support

group

solidarity.

The

few

inter-religious

marriages

that

do

occur

are

due

to

the

openness

of

Guyanese

society,

the

lack

of

purdah,

and

Muslim

women's

participation

in

the

labor

market.

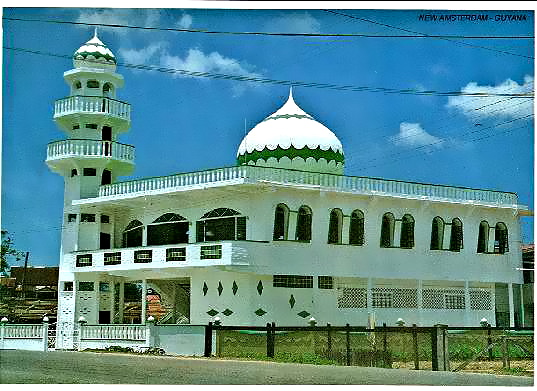

New

elements

derived

from

Middle

Eastern

culture,

such

as

architecture

of

the

mosque

and

its

dome,

have

been

introduced

as

part

of

the

Islamization

process.

Nevertheless,

`Indo-Iranian'

architecture

is

still

very

pronounced

in

the

style

of

mosques

throughout

Guyana.

Another

influence

is

the

manner

of

greeting

among

Muslim

men,

particularly

after

prayers

at

the

mosque,

which

involves

embracing

and

shaking

hands.

The

incorporation

of

Arabic

words

and

terms

instead

of

Urdu

words

and

terms

is

very

evident

today.

For

example,

instead

of

using

the

Urdu

word

bhai

(brother)

many

use

the

Arabic

term

akhee.

Guyanese

Muslim

who

can

afford

it

do

make

the

pilgrimage

to

Makkah.

Some

men

have

started

wearing

the

long

shirts

(jilbab)

which

they

acquired

after

the

pilgrimage

and

sport

long

beards.

Some

women

have

started

wearing

the

hijab,

or

head

scarf.

There

is a

move

toward

a

more

literary

tradition

in

conformity

with

Islam

at

the

expense

of

local

traditions.

In

this

religious

discourse,

the

interpretation

provided

by

orthodox

Muslims

relying

on

the

scriptural

tradition

seems

to

become

more

hegemonic,

creating

religious

authority

itself.

There

is

stronger

emphasis

on

the

need

to

learn

Arabic

for

the

namaz

(daily

worship)

and

on

correct

pronunciation,

as

well

as

the

ability

to

recite,

and

understand

the

Qur'an.

In

Guyana

today

the

emphasis

is

on

practicing

orthodox

and

Sunni

Islam.

This

is

voiced

by

many

imams

who

advocate

strict

adherence

to

the

Qur'an

and

the

Sunnah

of

the

Prophet.

However,

while

the

newly

returned

men

tend

to

convey

that

they

have

a

monopoly

on

religious

affairs,

they

have

so

far

failed

to

institutionalize

positive

changes.

Even

their

Bedouin

garb

intimidated

the

local

Muslim

population,

and

drew

more

fear

rather

than

respect

for

them.

These

`learned'

men

were

soon

forced

to

abandon

one

mosque

for

another

and

an

entire

realignment

took

place

in

Guyana.

New

organizations

were

formed

which

sought

to

make

changes

that

they

perceived

were

in

line

with

the

authentic

Islam

of

Arabia.

The

cleansing

of

the

`Indo-Iranian'

traditions

was

high

on

their

agenda,

and

continues

to

be

so.

In

1994

at

the

78

Corentyne

Mosque,

during

one

Eid,

two

separate

Eid

Namaz

were

held.

The

CIOG's

official

publication

Al-Bayan

writes,

`For

Eid-ul-Azha

1994,

the

Muslims

witnessed

a

very

sad

incident

that

clearly

indicated

that

the

#78

Jamaat

is

definitely

divided

into

two

factions'.(n33)

A

younger

imam

who

returned

from

Arabia

was

expelled

from

that

mosque.

This

division

led

to

the

resignation

of

Al-Haj

Mohamed

Ballie

as

imam.

Today

one

faction

is

building

a

new

mosque

nearby.

Al-Bayan

cited

a

similar

incident

at

the

Shieldstown

Jamat

in

1992:

`One

brother

was

physically

removed

from

the

masjid

because

he

refused

to

comply

with

the

ruling

of

the

Jamaat'.

(n34)

Most

Guyanese

Muslims

agree

that

it

would

be

wise

if

the

opponents

and

proponents

of

the

Indo-Iranian

tradition

seek

their

answers

from

the

Qur'an,

the

Sunnah

and

ijma'

(consensus),

instead

of

seeking

drastic

changes.

`

Despite

their

shortcomings

and

lack

of

formal

education,

the

early

Muslims

played

a

dynamic

role

in

maintaining

the

Islamic

society

and

paved

the

way

for

us

to

enjoy

the

benefits'.(n35)

For

the

younger

generation

everything

that

is

different

from

the

Arab

world

is

wrong.

They

fail

to

contemplate

that

from

Albania

to

Zanzibar

the

Muslim

world

speaks

many

languages

and

hails

from

many

different

traditions.

Here

in

Guyana,

they

tried

to

replace

Urdu

with

Arabic.

Instead

it

would

have

been

easier

to

build

upon

what

the

Guyanese

Muslims

had

knowledge

of

and

that

is

Urdu.

When

the

Muslims

arrived

in

Guyana

their

medium

of

communication

was

Urdu,

and

only

a

handful

could

read

and

write

Arabic.

In

fact

for

the

early

Muslims

Urdu

provided

the

basis

for

their

understanding

of

Islam

and

the

Qur'an.

Urdu

today

is a

dying

language

in

Guyana,

while

in

India

it

is

being

held

hostage

by

Hindu

zealots.

On

the

other

hand,

Arabic

has

not

made

any

significant